Consuming Public Content

A workflow enabling reliability, security, and performance

Developers are increasingly contributing to and consuming more public content for our container-based ecosystem. However, as community efforts of the past have proven, risks must be considered and mitigations put in place to protect the entire ecosystem, as well as your project, product, or service.

On November 1st, 2020, Docker Hub will begin limiting anonymous and free account image pulls. While some may be upset about the change, it reflects a larger reality that takes some consideration for the risks associated with consuming public content, not just the costs for hosting public content. Also please note that consumers who have a subscription do not have limits and the rate limiting is only for non-paying users.

As a community, the cloud providers, ISVs, and members of the OCI TOB co-authored this article to provide context, considerations as to how you might be impacted, and mitigations for the pending changes such as what you can do to avoid interruptions to your workflow.

Does This Apply to You

While this article focuses on Docker Hub, this also applies to any container image registry outside of you or your organization’s immediate control.

Do you use container based tooling:

docker buildFROM debian(or any other public image)?docker run nginx(or other public images)?helm install stable/cert-manager(or other helm charts that pull images from public registries)?

If so, this article applies to you.

Consuming Any Public Content

The overarching public content distribution problem isn’t limited to who should bear the cost for public content, but rather also encompasses who bears the responsibility of assuring the content is accessible and secure for your environment, 100% of the time. The recent Docker Terms of Service (TOS) changes encourage us to ask a broader set of questions that, as a community, we can address. The problem isn’t limited to production container images but extends to all package manager content (debs, rpms, rubygems, node modules, etc).

While the Docker TOS update directly imposes throttling on frequent non-authenticated and free account content pulls, which may impact critical workloads, it also raises the question of how and when public content should impact critical workloads.

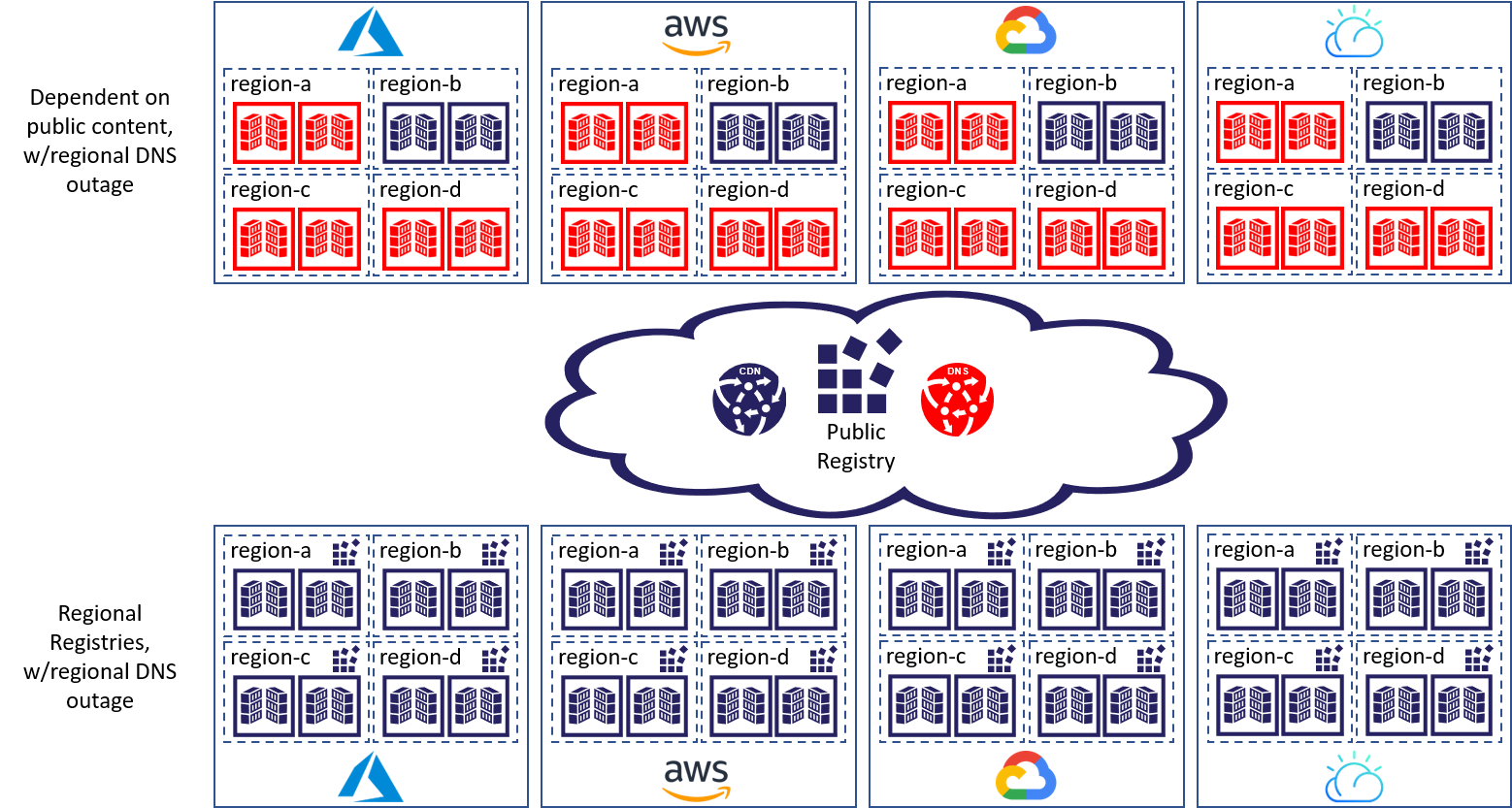

Single Points of Failure

Every application architect asks, where are the single points of failure and how can we mitigate them? As an example, in the top half of the below image, we see a DNS outage, indicated in red, that impacts regions a, c & d across all cloud providers. The DNS single point of failure impacted millions of users across multiple regions and multiple clouds. The lower half represents the same workloads, across all regions, where each region maintains a copy of the content they depend upon. The public content is still consumed, however, each customer maintains a copy of the content they depend upon within a registry they operate, thus avoiding the single point of failure.

Cost Doesn’t Mitigate Risk

If Docker, Quay, GitHub, or other public registries undertake the financial burden for serving content to the world, who bears the burden of reliability for all the connections between critical workloads and the public registry? Even if all inter-connections were 100% reliable 100% of the time and the risk of bad actors inserting vulnerabilities were not possible, who bears the impact of well-intentioned security updates causing an outage to critical workloads? As an example, when maintainers of the “node” image updated symbolic references to yarn, many consumers of the image were broken. While many focus on the underlying issue of using specific digests and tags to reference a desired version of a container image, this example highlighted the tension between getting security updates and the stability of content, for your environment. The question of access to public content isn’t just a matter of making public content cheap and reliably accessible, it’s a matter of creating gated buffers of the public content we depend upon.

Not Just Docker Images

Docker images aren’t the only type of public content we depend upon. Our eco-system regularly consumes content from javascript libraries; Npm, NuGet, rpm, Debian, maven, Helm charts, and other package managers; as well as public git sources and tarballs. So, is this a problem unique to container images? We submit there are two dimensions at play here; size(1) and frequency(2). Both dimensions apply to the dependent content our solutions need when running container images. Managing these assets has a direct impact on our production workloads that are designed to automatically self-heal and scale. When a workload automatically scales up, and a registry is inaccessible, due to DNS, CDN, or any other potential single points of failure, an immediate, and likely critical, production issue may occur. As pictured above, these single points of failure can directly impact multiple clouds, thousands of apps, and millions of end users (e.g. developers, consumers, downstream web sites, …).

Some parts of the ecosystem are not as drastically impacted by availability issues. For example, Npm, rpm, NuGet and other packages are smaller in size and are typically used as part of a build & test workflow. While an outage of package managers will fail builds and tests, frustrating DevOps engineers, these problems are typically gated by deployment validation(s), thus avoiding production outages and end-user impacts.

Mirrors Reflect the Good and the Bad

As registry operators, we are often asked to support a pull-through cache and/or registry mirror. While this type of availability improvement does mitigate some of the network reliability issues, and some registries implement mirrors, these types of improvements only partially cover the range of issues users face.

Example issues include:

- If the online content is accessible for the first request, subsequent requests can leverage the cached content. If the request is made during an outage, there is no guarantee the requested image is cached.

- If a tag is updated to a “broken” image, such as the node/yarn example, subsequent requests will pull the “broken” image. This begs the question, when the tag is updated to fix a first issue, at what point should the mirror know to update the cached reference?

- For those container image reference scenarios that pin to a digest (sha pointing to a specific image), how would you get the security update that you want and/or need if you are still pointing to an old version?

- With respect to customer-specific, authenticated-access-only container images that customers store on public registries, what are these customer’s expectations for caching and distribution of their authenticated content at the mirror or host?

While mirrors appear to reflect goodness, mirrors can create a false sense of security. When the connections are valid, they will bring the upstream changes to your local mirror, whether the change is what you want or not. As an example, it’s not always the technology that fails us, in some cases failures arise as a result of our human nature. As an example; Node modules are mirrored through global CDNs. Through a series of human interactions, one programmer broke the internet by deleting a tiny piece of “left-pad” code. In this case, the technology did just what it was asked, it mirrored the change.

What Are the Best Practices for Consuming Public Content

Consuming public content, including open source projects & paid content, is key to maintaining the development velocity by which developers are required to serve their users, which explains a Gartner study finding that 90% of software will include open source. While developers and consumers are pushing for velocity, our security and operations workers are pushing for a focus on the reliability and security of the public content.

To balance the consumption with velocity desired, against the reliability and security desires, we suggest adopting gated & verified workflows to enable the safe and secure use of rapidly deployed public content. While production deployments are the most obvious, maintaining a gated copy of the images you build FROM is just as important. Organizations should keep local copies of everything they depend upon, while building CI/CD workflows that update and validate their gated dependencies. For example, companies that maintained local gated copies of the javascript libraries they depend upon would have completely missed the production outages caused in the above cited example when the left-pad code was removed.

Short Term Throttling Mitigations

Maintaining a gated and verified copy of the content you require will take time to implement. As we head into the end-of-year holiday period, organizations tend to lock down their development and deployments.

When estimating the number of container image pull requests that may occur, take into account that when using cloud provider services or working behind a corporate NAT, multiple users will be presented to Docker Hub in aggregate as a subset of IP addresses. This means your first anonymous request for a container image may be the 101st anonymous request from a specific shared IP address in the last six hours. Consider what will happen if a Kubernetes pod restarts and can’t pull the image it needs into a critical workload. Adding Docker paid account authentication to requests made to Docker Hub is a sure way to avoid potential service disruptions due to the new rate limit throttling that Docker is introducing on the first of November, 2020.

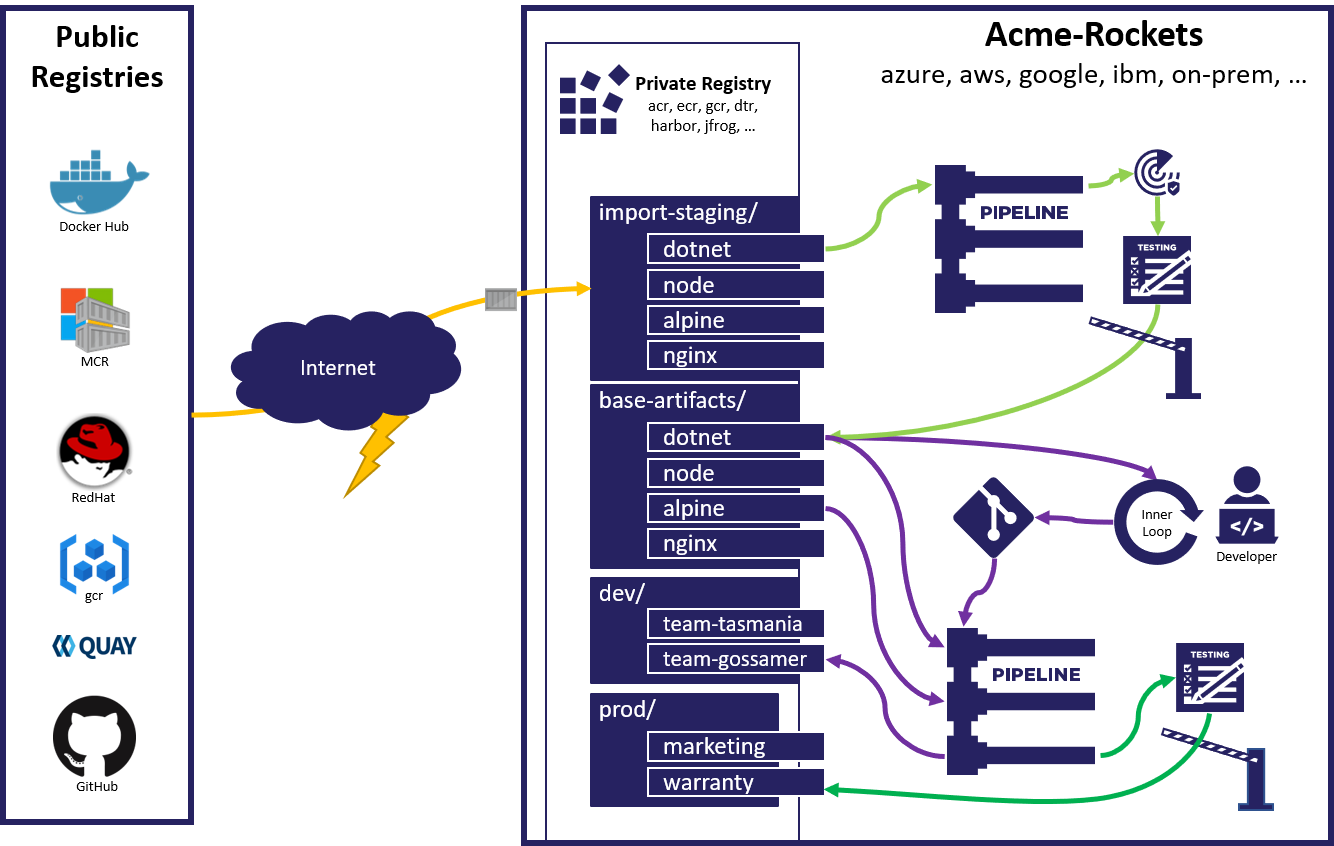

Longer-Term Gated Workflows

The Docker TOS updates give us an opportunity to focus on the larger challenges with consuming public content. If you depend on public content, we recommend configuring a workflow that imports the content, security scans the content based on your organization’s scanning policies, runs functional and integration tests to assure this most recent version of the content meets all expectations, then promote the validated content to a location your team(s) can utilize. The list of validations may start small, and evolve as new potential issues surface.

We also recommend implementing a scheduled job that periodically checks for updates, including security updates to existing tags. We further recommend to never let friends build against a :latest tag, if at all possible.

Over the next few months, we will bring focus to gated workflows, and proposals for how we can enable increased consumption of public content with reduced risk of the public content causing outages or negative impacts. We believe a set of standards for properly processing public content through gated workflows will help elevate the consumption of the content while enabling healthy competition on how to best implement and support these gated workflows. Building gated workflows enables developers and project teams to take more risk with respect to the velocity of change for public content.

Every public emergency (hurricanes, Covid-19, etc) reminds us of the importance of keeping critical supplies close to where we function. The content we store in registries is just another example of the same local-cache model employed by Emergency Services Teams.

Cloud & ISV Specific Guidance

Whether it’s a true exploit, well-intended security update, the result of humans being human, or some other type of risk to the public content of our ecosystem… the rigor we apply today to mitigating these risks is well worth the effort.

To understand how to implement Docker authenticated pulls, mitigating the Docker TOS changes, and how you can gate and buffer public content in your cloud provider, the following links are provided: